PSA Controversies

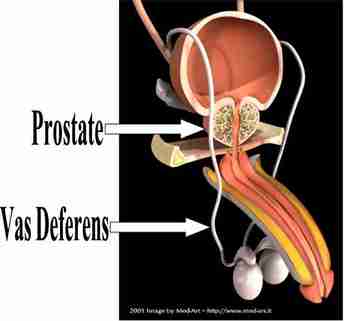

Quality-of-Life Effects of Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening

N Engl J Med 2012; 367:595-605 August 16, 2012

BACKGROUND

After 11 years of follow-up, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) reported a 29% reduction in prostate-cancer mortality among men who underwent screening for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. However, the extent to which harms to quality of life resulting from overdiagnosis and treatment counterbalance this benefit is uncertain.

RESULTS

Per 1000 men of all ages who were followed for their entire life span, we predicted that annual screening of men between the ages of 55 and 69 years would result in nine fewer deaths from prostate cancer (28% reduction), 14 fewer men receiving palliative therapy (35% reduction), and a total of 73 life-years gained (average, 8.4 years per prostate-cancer death avoided). The number of QALYs that were gained was 56 (range, −21 to 97), a reduction of 23% from unadjusted life-years gained. To prevent one prostate-cancer death, 98 men would need to be screened and 5 cancers would need to be detected. Screening of all men between the ages of 55 and 74 would result in more life-years gained (82) but the same number of QALYs (56).

CONCLUSIONS

The benefit of PSA screening was diminished by loss of QALYs owing to postdiagnosis long-term effects. Longer follow-up data from both the ERSPC and quality-of-life analyses are essential before universal recommendations regarding screening can be made.

N Engl J Med 2012; 367:595-605 August 16, 2012

BACKGROUND

After 11 years of follow-up, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) reported a 29% reduction in prostate-cancer mortality among men who underwent screening for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. However, the extent to which harms to quality of life resulting from overdiagnosis and treatment counterbalance this benefit is uncertain.

RESULTS

Per 1000 men of all ages who were followed for their entire life span, we predicted that annual screening of men between the ages of 55 and 69 years would result in nine fewer deaths from prostate cancer (28% reduction), 14 fewer men receiving palliative therapy (35% reduction), and a total of 73 life-years gained (average, 8.4 years per prostate-cancer death avoided). The number of QALYs that were gained was 56 (range, −21 to 97), a reduction of 23% from unadjusted life-years gained. To prevent one prostate-cancer death, 98 men would need to be screened and 5 cancers would need to be detected. Screening of all men between the ages of 55 and 74 would result in more life-years gained (82) but the same number of QALYs (56).

CONCLUSIONS

The benefit of PSA screening was diminished by loss of QALYs owing to postdiagnosis long-term effects. Longer follow-up data from both the ERSPC and quality-of-life analyses are essential before universal recommendations regarding screening can be made.

To operate or not to operate ?

Prostatectomy vs. Observation for Prostate Cancer: PIVOT

Allan S. Brett, MD

Posted: 09/10/2012; Journal Watch © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society

Abstract - Prostatectomy did not lower 10-year mortality overall; the exception was men with PSA levels >10 ng/mL.

Introduction - Until now, no randomized trial has been designed to compare surgery with "watchful waiting" in patients with primarily prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-detected, localized prostate cancer. PIVOT (Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial), conducted in the U.S., fills this gap.

The participants — 731 men with localized prostate cancer and life expectancy of at least 10 years — were randomized to radical prostatectomy or observation. Three quarters of cases were diagnosed through PSA screening, two thirds of men had PSA levels ≤10 ng/mL, and two thirds had Gleason scores <7. During the study, 10% of men in the observation group crossed over to prostatectomy.

At median follow-up of 10 years, neither all-cause mortality nor prostate cancer–specific mortality was significantly lower in the prostatectomy group than in the observation group. However, among men with PSA levels >10 ng/mL, mortality was lower with prostatectomy ( Table ). Subgroups with higher-risk cancers (defined by criteria incorporating PSA levels, Gleason scores, and tumor staging) also showed trends toward lower mortality with surgery. Bone metastases occurred in 4.7% of prostatectomy patients and in 10.6% of observation patients (P<0.001).

Interpretation of these results likely will depend on one's preconceptions. Clinicians predisposed to no intervention will emphasize the overall results, which suggest low probability of benefiting from radical prostatectomy. Clinicians predisposed to aggressive intervention will note that prostatectomy was associated with significantly lower 10-year mortality in prespecified subgroups. Some people will argue that PIVOT was underpowered; indeed, it fell short of its original enrollment goal of 2000 participants. Nevertheless, these findings comprise the best available data and should be used by urologists, oncologists, and primary care physicians to guide clinical decision making. Finally, given that surgery was ineffective for men with PSA levels ≤10 ng/mL, it will be interesting to see whether PSA screening supporters will revise upward their favored PSA thresholds for triggering biopsy.

Allan S. Brett, MD

Posted: 09/10/2012; Journal Watch © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society

Abstract - Prostatectomy did not lower 10-year mortality overall; the exception was men with PSA levels >10 ng/mL.

Introduction - Until now, no randomized trial has been designed to compare surgery with "watchful waiting" in patients with primarily prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-detected, localized prostate cancer. PIVOT (Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial), conducted in the U.S., fills this gap.

The participants — 731 men with localized prostate cancer and life expectancy of at least 10 years — were randomized to radical prostatectomy or observation. Three quarters of cases were diagnosed through PSA screening, two thirds of men had PSA levels ≤10 ng/mL, and two thirds had Gleason scores <7. During the study, 10% of men in the observation group crossed over to prostatectomy.

At median follow-up of 10 years, neither all-cause mortality nor prostate cancer–specific mortality was significantly lower in the prostatectomy group than in the observation group. However, among men with PSA levels >10 ng/mL, mortality was lower with prostatectomy ( Table ). Subgroups with higher-risk cancers (defined by criteria incorporating PSA levels, Gleason scores, and tumor staging) also showed trends toward lower mortality with surgery. Bone metastases occurred in 4.7% of prostatectomy patients and in 10.6% of observation patients (P<0.001).

Interpretation of these results likely will depend on one's preconceptions. Clinicians predisposed to no intervention will emphasize the overall results, which suggest low probability of benefiting from radical prostatectomy. Clinicians predisposed to aggressive intervention will note that prostatectomy was associated with significantly lower 10-year mortality in prespecified subgroups. Some people will argue that PIVOT was underpowered; indeed, it fell short of its original enrollment goal of 2000 participants. Nevertheless, these findings comprise the best available data and should be used by urologists, oncologists, and primary care physicians to guide clinical decision making. Finally, given that surgery was ineffective for men with PSA levels ≤10 ng/mL, it will be interesting to see whether PSA screening supporters will revise upward their favored PSA thresholds for triggering biopsy.

Some Expert Comments on the PIVOT Trial

" They reported on PIVOT (Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial), which compared radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting in men with clinically localized disease and a negative bone scan. They enrolled 731 men with a mean age of 67 years and a mean prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 7.8 ng/mL.

The results are likely to stir up a lot more controversy. The authors found that when they looked at overall survival or prostate cancer-specific survival, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups. The absolute difference that they observed was 2.9% for overall survival and 2.6% for prostate cancer survival. That translates into about 1 out of 34 men benefitting in overall survival and 1 out of 38 benefitting in terms of reduced prostate cancer mortality. Subset analyses showed that for men who had either low-risk prostate cancer or PSA levels less than 10 ng/mL, there was no benefit from surgery and maybe even slightly worse overall survival and prostate cancer survival.

A benefit for men who had high-risk disease or PSA levels > 10 ng/mL was suggested. The problem is that when the investigators did a central pathology analysis, the apparent benefit disappeared. The robust data seem to be limited to the results for PSA.

This study will engender several critiques that are worth discussing. Number one, was it powered enough to see a significant difference? The authors stated that they had a 91% chance of detecting a 25% difference, but what about a difference of only 10%? What power would they have had to have to see that, should it exist?

Another critique is that not all of the men complied, which is true for every clinical randomized trial. Overall compliance, which was about 80%, was similar to that seen in the Scandinavian trial, [2] which did find a small but significant difference in survival for men under the age of 65 years getting surgery and no benefit for men who were older.

Another critique has been about the applicability of these results to the general population today. We need to keep in mind that when the study was started in 1994, the threshold for doing biopsies was a little higher in terms of PSA, men were not subjected to as many repeat biopsies, and the number of cores was in the process of being changed. Men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer today are much more likely to have smaller-volume disease because the PSA threshold has changed, biopsies are done with a greater number of needles, and the threshold is lower than it was back then.

So where does this leave us? It leaves us with some interesting and challenging messages. Certainly, any man who is considering getting screened for prostate cancer should be aware of these findings. It might mean that we shouldn't perform biopsies on men until their PSA level exceeds 10 ng/mL. Although it is true that they are more likely to have disease that is outside of the prostate, they are also more likely to have a tumor that can benefit from being treated aggressively. By doing that, the number of men getting unnecessary treatment that is not offering any benefit would be limited.

It is absolutely critical that we make sure that every man diagnosed with prostate cancer is aware of these results. Men who are at low risk or men with a PSA level < 10 ng/mL have a strong consideration to pursue active surveillance far before considering aggressive therapy. The study data emphasized the fact that these low-risk men or men with a low PSA are not benefitting significantly by being treated aggressively, but that they are at risk for significant side effects, which will be discussed in a future paper.

At the end of the day, we are getting good information from this well-done randomized trial. Although it took a long time to accrue the necessary number of men, both groups were balanced in terms of all the potential risk factors. I think that this is important new information that needs to be shared with our patients. The challenge is to make sure that patients hear this information in a balanced fashion before they end up with treatment.

I look forward to your comments. Thank you."

Gerald Chodak, Midwest Prostate Center

The results are likely to stir up a lot more controversy. The authors found that when they looked at overall survival or prostate cancer-specific survival, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups. The absolute difference that they observed was 2.9% for overall survival and 2.6% for prostate cancer survival. That translates into about 1 out of 34 men benefitting in overall survival and 1 out of 38 benefitting in terms of reduced prostate cancer mortality. Subset analyses showed that for men who had either low-risk prostate cancer or PSA levels less than 10 ng/mL, there was no benefit from surgery and maybe even slightly worse overall survival and prostate cancer survival.

A benefit for men who had high-risk disease or PSA levels > 10 ng/mL was suggested. The problem is that when the investigators did a central pathology analysis, the apparent benefit disappeared. The robust data seem to be limited to the results for PSA.

This study will engender several critiques that are worth discussing. Number one, was it powered enough to see a significant difference? The authors stated that they had a 91% chance of detecting a 25% difference, but what about a difference of only 10%? What power would they have had to have to see that, should it exist?

Another critique is that not all of the men complied, which is true for every clinical randomized trial. Overall compliance, which was about 80%, was similar to that seen in the Scandinavian trial, [2] which did find a small but significant difference in survival for men under the age of 65 years getting surgery and no benefit for men who were older.

Another critique has been about the applicability of these results to the general population today. We need to keep in mind that when the study was started in 1994, the threshold for doing biopsies was a little higher in terms of PSA, men were not subjected to as many repeat biopsies, and the number of cores was in the process of being changed. Men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer today are much more likely to have smaller-volume disease because the PSA threshold has changed, biopsies are done with a greater number of needles, and the threshold is lower than it was back then.

So where does this leave us? It leaves us with some interesting and challenging messages. Certainly, any man who is considering getting screened for prostate cancer should be aware of these findings. It might mean that we shouldn't perform biopsies on men until their PSA level exceeds 10 ng/mL. Although it is true that they are more likely to have disease that is outside of the prostate, they are also more likely to have a tumor that can benefit from being treated aggressively. By doing that, the number of men getting unnecessary treatment that is not offering any benefit would be limited.

It is absolutely critical that we make sure that every man diagnosed with prostate cancer is aware of these results. Men who are at low risk or men with a PSA level < 10 ng/mL have a strong consideration to pursue active surveillance far before considering aggressive therapy. The study data emphasized the fact that these low-risk men or men with a low PSA are not benefitting significantly by being treated aggressively, but that they are at risk for significant side effects, which will be discussed in a future paper.

At the end of the day, we are getting good information from this well-done randomized trial. Although it took a long time to accrue the necessary number of men, both groups were balanced in terms of all the potential risk factors. I think that this is important new information that needs to be shared with our patients. The challenge is to make sure that patients hear this information in a balanced fashion before they end up with treatment.

I look forward to your comments. Thank you."

Gerald Chodak, Midwest Prostate Center

Overtreatment of Prostate Cancer

Stats Don't Lie: --Avoiding Overtreatment of Prostate Cancer

Edwin Darracott Vaughan, MD

Management of Low (Favourable)-Risk Prostate CancerCarter

BJU Int. 2011;108:1684-1695

Introduction The most significant development in urology last year was the surprising recommendation from the US Preventive Services Task Force that routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in healthy men is not indicated for early detection of prostate cancer.[1] That draft recommendation has been soundly criticized in some circles and will probably be modified before it is finalized.

The rationale behind the recommendation, however, was the lack of randomized clinical trials showing that early detection leads to fewer cancer-specific deaths. Furthermore, early detection has led to overtreatment of patients with low-grade, low-risk cancer, in whom the side effects of prostate biopsy and subsequent treatment negatively outweigh the gain in cancer-specific survival, especially in elderly patients.

Evidence of this disconnect was seen in the National Cancer Institute's Patterns of Care Study,[2] which found that 71% of men older than 75 years with favorable-risk disease received radiotherapy. Only 12% were managed with active surveillance.

Of course, the good news is that most patients identified through early screening have curable, localized disease, and the mortality rate from prostate cancer has decreased 30%-40% in the PSA era.[3]

Study Summary

In this excellent article, Carter provides current statistics on the treatment of patients with low-risk disease and discusses definitions of "low-risk" disease and current guidance for pursuing close observation rather than immediate intervention.

Can we define low-risk disease? Carter reviews 2 classification schemes from D'Amico and colleagues[4] and Epstein and colleagues[5] that have stood the test of time. However, there has been significant upgrading on surgical specimens, which has led to the recommendation for repeated biopsies in patients receiving close observation.

What do we know about patients with low-risk prostate cancer? Currently, patients with localized low-risk disease should be given the option of close observation. They should be informed that intervention with surgery or radiation reduces cancer-specific mortality by 50%, but that their cancer-specific mortality risk without treatment is less than 10%. These patients also need to be aware that the risk for cancer spread is low but does exist.

In the longest prospective study of 450 men followed with active surveillance for a median of 7 years, 10-year actuarial cancer-specific survival was 97% (and 17% of the patients were not low risk on entry).[6] Also, in a multi-institutional study, the 5-year probability of a patient remaining on active surveillance was 75%.[7]

In the future, identification of new molecular markers will give us a better definition of low-risk prostate cancer. At the present time, however, patients with low-risk disease should be informed about the pros and cons of close observation. Carter offers guidance for urologists in helping patients make an informed treatment choice.

Edwin Darracott Vaughan, MD

Management of Low (Favourable)-Risk Prostate CancerCarter

BJU Int. 2011;108:1684-1695

Introduction The most significant development in urology last year was the surprising recommendation from the US Preventive Services Task Force that routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in healthy men is not indicated for early detection of prostate cancer.[1] That draft recommendation has been soundly criticized in some circles and will probably be modified before it is finalized.

The rationale behind the recommendation, however, was the lack of randomized clinical trials showing that early detection leads to fewer cancer-specific deaths. Furthermore, early detection has led to overtreatment of patients with low-grade, low-risk cancer, in whom the side effects of prostate biopsy and subsequent treatment negatively outweigh the gain in cancer-specific survival, especially in elderly patients.

Evidence of this disconnect was seen in the National Cancer Institute's Patterns of Care Study,[2] which found that 71% of men older than 75 years with favorable-risk disease received radiotherapy. Only 12% were managed with active surveillance.

Of course, the good news is that most patients identified through early screening have curable, localized disease, and the mortality rate from prostate cancer has decreased 30%-40% in the PSA era.[3]

Study Summary

In this excellent article, Carter provides current statistics on the treatment of patients with low-risk disease and discusses definitions of "low-risk" disease and current guidance for pursuing close observation rather than immediate intervention.

Can we define low-risk disease? Carter reviews 2 classification schemes from D'Amico and colleagues[4] and Epstein and colleagues[5] that have stood the test of time. However, there has been significant upgrading on surgical specimens, which has led to the recommendation for repeated biopsies in patients receiving close observation.

What do we know about patients with low-risk prostate cancer? Currently, patients with localized low-risk disease should be given the option of close observation. They should be informed that intervention with surgery or radiation reduces cancer-specific mortality by 50%, but that their cancer-specific mortality risk without treatment is less than 10%. These patients also need to be aware that the risk for cancer spread is low but does exist.

In the longest prospective study of 450 men followed with active surveillance for a median of 7 years, 10-year actuarial cancer-specific survival was 97% (and 17% of the patients were not low risk on entry).[6] Also, in a multi-institutional study, the 5-year probability of a patient remaining on active surveillance was 75%.[7]

In the future, identification of new molecular markers will give us a better definition of low-risk prostate cancer. At the present time, however, patients with low-risk disease should be informed about the pros and cons of close observation. Carter offers guidance for urologists in helping patients make an informed treatment choice.