Amazing ASA

Picture a wonder drug that can prevent a third of all cancers.

And also decreases heart attack risk by about 30 % in high risk patients

And also prevents strokes.

And even delays or eliminates Alzheimer's

It's even good for sore joints, headaches and fevers.

And best of all - it is organic !

Aspirin is now over a hundred years old, but remains one of the most useful oldtimers of all time. In Irish terms it is "good for what ails you".

And also decreases heart attack risk by about 30 % in high risk patients

And also prevents strokes.

And even delays or eliminates Alzheimer's

It's even good for sore joints, headaches and fevers.

And best of all - it is organic !

Aspirin is now over a hundred years old, but remains one of the most useful oldtimers of all time. In Irish terms it is "good for what ails you".

Executiv Summary of ASA knowledge to date

1) Low dose aspirin cuts risk of heart attack and most stroke dramatically within 30 minutes of the first tablet. And the tablet can be the 81 mg "baby aspirin" strength.

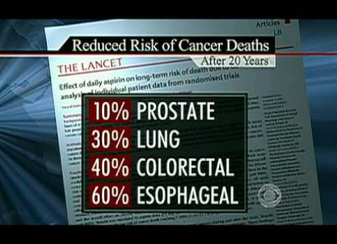

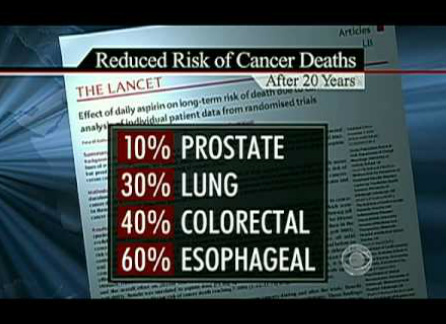

2) ASA prevents cancer, in what seems to be a dose related fashion. So more ASA probably prevents more cancer ( especially gastro-intestinal malignancies).

3) ASA helps to prevent Alzheimers disease if taken regularly in mid life ( daily ASA for a minimum of four years)

4) ASA may not prevent heart attacks and strokes in women and diabetics, or they may just require higher doses that the usual baby aspirin strength. ( Diabetics and women may have blood that is clumpier than usual geezer men. )

5) The down side of the anti-clotting effect of ASA is that you bleed easier. So the balance of whether or not you should be on ASA depends on your individual risk factors for bleeding, clotting, and inflammation. It is something you can discuss with your family doctor, who can calculate a "risk score" for you to say whether you are likely to do better on the ASA or off of it !

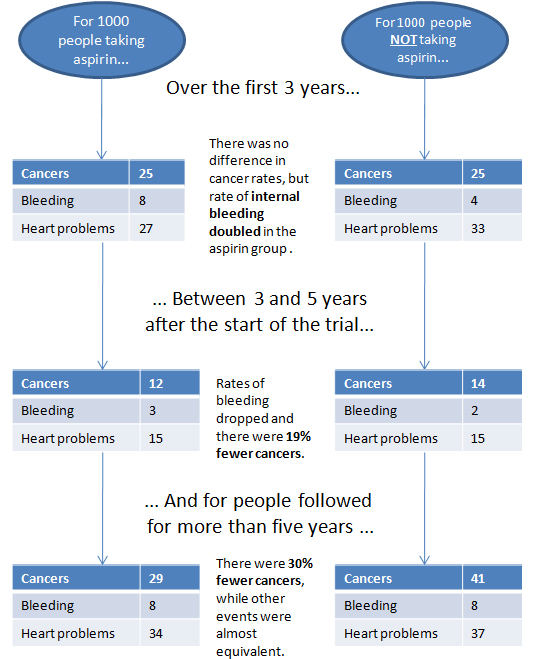

Measuring the heart attack and stroke and cancer prevention and Alzheimer's benefits all together.

One of my pet peeves is that no one actually studies all this. Because the specialists who do all the studies tend to focus only on their own area of interest, and not the patient overall. Lots of chunks, no whole.

However .... they are finally catching on. We now have some accurate statistics to measure how much benefit is taking into account both the combined effects of cardiac prevention and cancer prevention.

A meta-analysis ( this is a fancy statistical analysis ) addressing this combined

outcome suggests that aspirin use in 1000 average risk patients at age 60 years

would be expected to result, over a 10-year period, in 6 fewer deaths, 19

fewer non-fatal myocardial infarctions, 14 fewer cancers, and 16 more major

bleeding events (table 1).

For individuals age 50 years or greater without excess bleeding risks, we suggest daily aspirin at a dose of 75 to 100 mg. Most folks take 81 mg. because that is what the drugstores sell, because that is the strength of the old "baby aspirin".

Patients who are more concerned about the bleeding risks than the potential benefits may reasonably choose to not take aspirin for primary prevention. To find out what your risk is, see your family doctor.

Or, if you look around heard enough, there is actually a place on this web site where you can calculate it.

2) ASA prevents cancer, in what seems to be a dose related fashion. So more ASA probably prevents more cancer ( especially gastro-intestinal malignancies).

3) ASA helps to prevent Alzheimers disease if taken regularly in mid life ( daily ASA for a minimum of four years)

4) ASA may not prevent heart attacks and strokes in women and diabetics, or they may just require higher doses that the usual baby aspirin strength. ( Diabetics and women may have blood that is clumpier than usual geezer men. )

5) The down side of the anti-clotting effect of ASA is that you bleed easier. So the balance of whether or not you should be on ASA depends on your individual risk factors for bleeding, clotting, and inflammation. It is something you can discuss with your family doctor, who can calculate a "risk score" for you to say whether you are likely to do better on the ASA or off of it !

Measuring the heart attack and stroke and cancer prevention and Alzheimer's benefits all together.

One of my pet peeves is that no one actually studies all this. Because the specialists who do all the studies tend to focus only on their own area of interest, and not the patient overall. Lots of chunks, no whole.

However .... they are finally catching on. We now have some accurate statistics to measure how much benefit is taking into account both the combined effects of cardiac prevention and cancer prevention.

A meta-analysis ( this is a fancy statistical analysis ) addressing this combined

outcome suggests that aspirin use in 1000 average risk patients at age 60 years

would be expected to result, over a 10-year period, in 6 fewer deaths, 19

fewer non-fatal myocardial infarctions, 14 fewer cancers, and 16 more major

bleeding events (table 1).

For individuals age 50 years or greater without excess bleeding risks, we suggest daily aspirin at a dose of 75 to 100 mg. Most folks take 81 mg. because that is what the drugstores sell, because that is the strength of the old "baby aspirin".

Patients who are more concerned about the bleeding risks than the potential benefits may reasonably choose to not take aspirin for primary prevention. To find out what your risk is, see your family doctor.

Or, if you look around heard enough, there is actually a place on this web site where you can calculate it.

For a 2014 summary of the risks and benefits of aspirin, here is a movie by a bunch of geeky guys in labcoats, who are a wee bit conservative, but are telling the absolute truth, as of Aug 2014.

Click on the picture at left to see the video.

Click on the picture at left to see the video.

How does aspirin find the headache ?

This is a question patients ask me regularly. How does aspirin know exactly where to go to find the red, sore, inflamed joint, headache, or whatever ?

This conjures up the mental image of tiny aspirin molecules all equipped with maps and compasses advancing through the bloodstream. (Of course, if they were guy aspirin molecules, they would rather die or convert to Tylenol than ask directions. )

Being able to find the achy spot is going to become an increasingly important question as the baby boom generation limps into middle age, and all our joints start to creak and squeak. Three million Canadians already suffer from some type of arthritis. By the year 2020 the number will be 6.5 million. Put another way, three hundred new cases of arthritis are diagnosed every day. These joint pains cost the Canadian economy approximately 8.5 billion dollars a year. The average worker with rheumatoid arthritis loses three to four years of total working time.

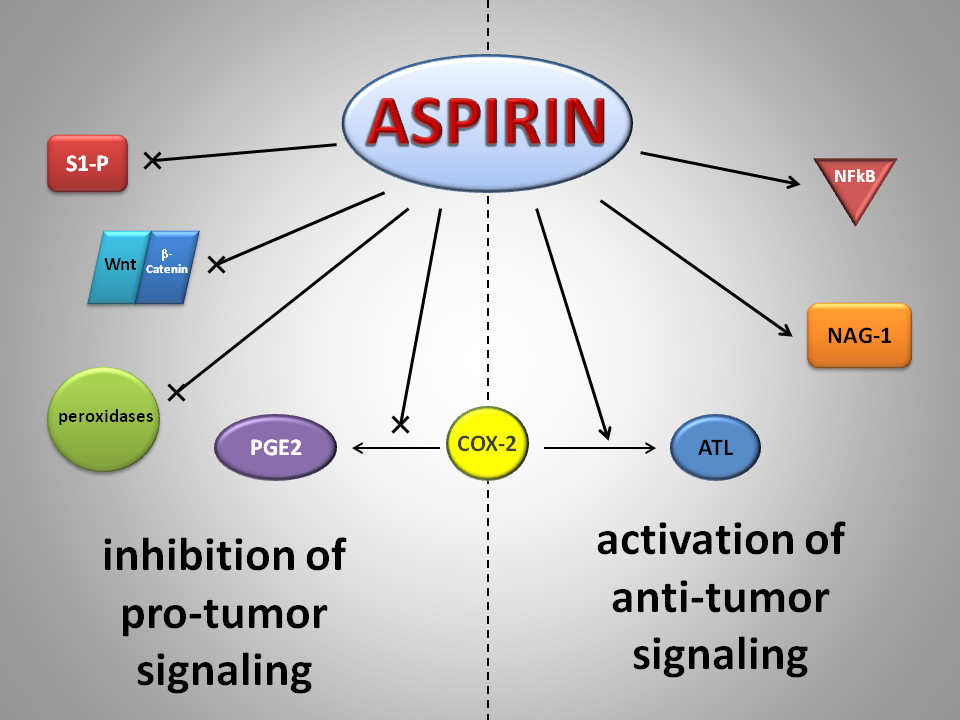

Fortunately the cause of all these miseries has been discovered - in the prostate. Arthritic joints feel like they are on fire. They are, and it is a chemical fire. Almost all of the symptoms in acute arthritis come from chemicals called “prostaglandins” - they are called this because they were first discovered lurking in the depths of the prostate gland. Prostaglandins are the biochemical equivalent of napalm poured into the joints. They cause joints to swell up, and become red, tender, and painful. If we could prevent the making of prostaglandins in painful joints then we would be able to relieve an enormous amount of pain and suffering.

This is exactly how anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin work. Drugs which inhibit be production of prostaglandins are referred to as “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs”, or “NSAIDS. Inhibiting prostaglandin-induced inflammation is a wonderful way of preventing pain and swelling. Rather than just numbing your mind to the pain (as narcotic painkillers do), anti-inflammatory medications actually decrease pain at the source. Because they affect pain at the level of the joint rather than the brain, they do not affect alertness or concentration.

This means that they can be used while working, driving, or operating machinery, and have no appreciable effect on alertness or reaction time. Without these anti-inflammatory medications we would be a much stiffer and sorer society. But not all prostaglandins are bad. Some of them are helpful to us. They help our kidneys and blood to function properly, and they protect our stomachs. Therefore, when we interfere with the production of all prostaglandins, we do so at the risk of our kidneys, blood, and stomachs.

This conjures up the mental image of tiny aspirin molecules all equipped with maps and compasses advancing through the bloodstream. (Of course, if they were guy aspirin molecules, they would rather die or convert to Tylenol than ask directions. )

Being able to find the achy spot is going to become an increasingly important question as the baby boom generation limps into middle age, and all our joints start to creak and squeak. Three million Canadians already suffer from some type of arthritis. By the year 2020 the number will be 6.5 million. Put another way, three hundred new cases of arthritis are diagnosed every day. These joint pains cost the Canadian economy approximately 8.5 billion dollars a year. The average worker with rheumatoid arthritis loses three to four years of total working time.

Fortunately the cause of all these miseries has been discovered - in the prostate. Arthritic joints feel like they are on fire. They are, and it is a chemical fire. Almost all of the symptoms in acute arthritis come from chemicals called “prostaglandins” - they are called this because they were first discovered lurking in the depths of the prostate gland. Prostaglandins are the biochemical equivalent of napalm poured into the joints. They cause joints to swell up, and become red, tender, and painful. If we could prevent the making of prostaglandins in painful joints then we would be able to relieve an enormous amount of pain and suffering.

This is exactly how anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin work. Drugs which inhibit be production of prostaglandins are referred to as “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs”, or “NSAIDS. Inhibiting prostaglandin-induced inflammation is a wonderful way of preventing pain and swelling. Rather than just numbing your mind to the pain (as narcotic painkillers do), anti-inflammatory medications actually decrease pain at the source. Because they affect pain at the level of the joint rather than the brain, they do not affect alertness or concentration.

This means that they can be used while working, driving, or operating machinery, and have no appreciable effect on alertness or reaction time. Without these anti-inflammatory medications we would be a much stiffer and sorer society. But not all prostaglandins are bad. Some of them are helpful to us. They help our kidneys and blood to function properly, and they protect our stomachs. Therefore, when we interfere with the production of all prostaglandins, we do so at the risk of our kidneys, blood, and stomachs.

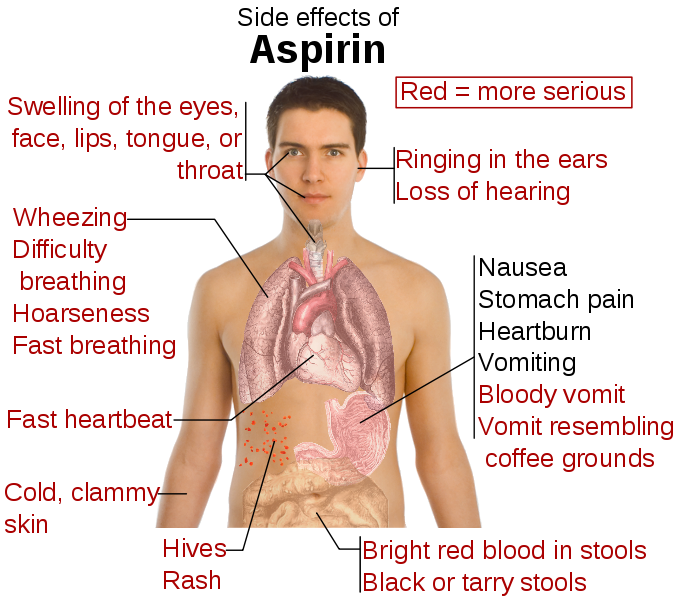

ASA complications

This is why people who are on long-term aspirin or some other anti-inflammatory medication are at risk for kidney problems, bleeding disorders, and ulcers. An anti-inflammatory medication may decrease the swelling of a joint, but at the same time create an ulcer in the stomach lining. This risk of bleeding ulcers from NSAIDS is estimated at between two percent and four percent per year. This does not sound like much, but the statistics are that more people in Canada die from the complications of anti-inflammatory medications (mostly bleeding ulcers ) than die from car accidents, drowning, and cold exposure all combined.

And two thirds of serious ulcers come from aspirin or ibuprofen - the non-prescription anti-inflammatories that we mistake as being safe to take lightly. In order to have the benefits of anti-inflammatory medications without dangerous side effects we have to use them wisely. Anti-inflammatory medications should always be taken with food so as to minimize stomach irritation. Patients who have kidney problems or high blood pressure should be monitored closely by their family doctor while taking anti-inflammatory medication.

Patients should be wary of combining anti-inflammatory medication with other medications. The ideal situation would be if we could design and anti-inflammatory drug which would only affect the bad prostaglandins in joints and acute illnesses, and not interfere with the good prostaglandins that protect our stomach and kidneys. This may have just happened -- the very newest anti-inflammatory medications appear to be safe for our stomachs.

And two thirds of serious ulcers come from aspirin or ibuprofen - the non-prescription anti-inflammatories that we mistake as being safe to take lightly. In order to have the benefits of anti-inflammatory medications without dangerous side effects we have to use them wisely. Anti-inflammatory medications should always be taken with food so as to minimize stomach irritation. Patients who have kidney problems or high blood pressure should be monitored closely by their family doctor while taking anti-inflammatory medication.

Patients should be wary of combining anti-inflammatory medication with other medications. The ideal situation would be if we could design and anti-inflammatory drug which would only affect the bad prostaglandins in joints and acute illnesses, and not interfere with the good prostaglandins that protect our stomach and kidneys. This may have just happened -- the very newest anti-inflammatory medications appear to be safe for our stomachs.

Misc. Info

This is such a boon to treatment of joint pains that the first drug of this new type has had more instant popularity then any other drug introduced to the market, with the exceptions of Prozac and Viagra. Although it doesn't get rid of the kidney and blood side effects, it definitely is kind to your tummy.

Our anti-inflammatory molecules have finally learned to have a better sense of direction. They find the sore joints quickly and efficiently, and never ever get lost in the stomach.

Now if we could only get them to talk about their feelings!

Dr. Patrick Nesbitt

Our anti-inflammatory molecules have finally learned to have a better sense of direction. They find the sore joints quickly and efficiently, and never ever get lost in the stomach.

Now if we could only get them to talk about their feelings!

Dr. Patrick Nesbitt

Aspirin prevents Cancer

CLICK ON THE PICTURE TO WATCH THE VIDEO

An aspirin a day can keep cancer away.

Amazing but true. Click on the picture at the left to seem some video details, or read the boring medical journal article below !

Background A recent pooled analysis of randomized trials of daily aspirin for prevention of vascular events found a substantial reduction (relative risk [RR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.49 to 0.82) in overall cancer mortality during follow-up occurring after 5 years on aspirin. However, the magnitude of the effect of daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, on cancer mortality is uncertain.

Results Compared with no use, daily aspirin use at baseline was associated with slightly lower cancer mortality, regardless of duration of daily use, although those who have been regular users for over five years had the greatest reduction in cancer mortality - up to 37% less deaths from all forms of cancer. The effect occurred both with low dose and regular dose aspirin.

To quote one of the more recent studies directly "If these results are accurate and generalizable, people who begin a long-term regimen of daily low-dose aspirin and continue use for 5 years could reduce their subsequent risk of dying from cancer by more than a third ...."

Logically, the more aspirin that you take and the longer the amount of time you have taken it the more of a cancer protecting effect. But daily dosing seems to be important. While it is still being studied, taking alternate day aspirin does not seem to have the same protective effect (for <5 years of use, RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.85 to 1.01; for ≥5 years of use, RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.83 to 1.02). Associations were slightly stronger in analyses that used updated aspirin information from periodic follow-up questionnaires and included 3373 cancer deaths (for <5 years of use, RR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.76 to 0.94; for ≥5 years of use, RR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.75 to 0.95).

Conclusion These results are consistent with an association between recent daily aspirin use and modestly lower cancer mortality but suggest that any reduction in cancer mortality may be smaller than that observed with long-term aspirin use in the pooled trial analysis.

IntroductionA recent pooled analysis of randomized trials of daily aspirin for prevention of vascular events by Rothwell et al.[1]reported a statistically significant 15% reduction in overall cancer mortality during an intervention period of up to 10 years. The overall reduction in cancer mortality was mostly attributable to an estimated 37% reduction in cancer mortality during follow-up occurring after 5 years on aspirin (relative risk [RR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.49 to 0.82; 92 cancer deaths in the aspirin group compared with 142 in the control group). Similar effects were observed for lower doses, mostly 75–100mg/day, and higher doses (≥300mg/day).

In contrast to the pooled analysis of trials of daily aspirin,[1] two very large randomized trials of alternate-day aspirin observed no effect on overall cancer mortality,[2,3] raising questions about the frequency of aspirin use needed to reduce cancer risk. The Physicians' Health Study tested 325mg of aspirin every other day for 5 years and reported a relative risk of 1.16 (95% CI = 0.84 to 1.61, 79 cancer deaths on aspirin compared with 68 on placebo).[2] The Women's Health Study tested a lower dose (100mg every other day) for 10 years and reported a relative risk of 0.95 (95% CI = 0.81 to 1.11, 284 cancer deaths on aspirin compared with 299 on placebo).[3] Three large observational studies of aspirin use and cancer mortality reported mixed results,[4–6] although none of these studies examined aspirin use that was both long term and daily.

Results from the pooled trial analysis[1] potentially have very important implications. If these results are accurate and generalizable, people who begin a long-term regimen of daily low-dose aspirin and continue use for 5 years could reduce their subsequent risk of dying from cancer by more than a third. However, uncertainty remains about the magnitude of the effect of daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, on cancer mortality. In the pooled trial analysis,[1] the relative risk estimate for cancer mortality occurring during follow-up after the first 5 years was based on limited numbers and therefore included a relatively wide confidence interval. In addition, the magnitude of the association with overall cancer mortality is larger than might have been expected, given the absence of apparent effects on cancer mortality in large trials of aspirin taken every other day[2,3] and results from observational studies suggesting that aspirin use does not strongly reduce risk of cancers other than colorectal, esophageal, and stomach cancers.[7]

The purpose of this analysis was to quantify the association between daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, and overall cancer mortality in the Cancer Prevention Study II (CPS-II) Nutrition Cohort, making use of detailed information on aspirin use collected at multiple time points. Because of the notable 37% reduction in cancer mortality observed in the pooled trial analysis during follow-up occurring after 5 years on daily aspirin,[1] we were particularly interested in cancer mortality among individuals in our cohort with a comparable history of aspirin exposure, that is, current daily aspirin users who had used aspirin during the preceding 5 years (referred to as current daily users of ≥5 years).

Amazing but true. Click on the picture at the left to seem some video details, or read the boring medical journal article below !

Background A recent pooled analysis of randomized trials of daily aspirin for prevention of vascular events found a substantial reduction (relative risk [RR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.49 to 0.82) in overall cancer mortality during follow-up occurring after 5 years on aspirin. However, the magnitude of the effect of daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, on cancer mortality is uncertain.

Results Compared with no use, daily aspirin use at baseline was associated with slightly lower cancer mortality, regardless of duration of daily use, although those who have been regular users for over five years had the greatest reduction in cancer mortality - up to 37% less deaths from all forms of cancer. The effect occurred both with low dose and regular dose aspirin.

To quote one of the more recent studies directly "If these results are accurate and generalizable, people who begin a long-term regimen of daily low-dose aspirin and continue use for 5 years could reduce their subsequent risk of dying from cancer by more than a third ...."

Logically, the more aspirin that you take and the longer the amount of time you have taken it the more of a cancer protecting effect. But daily dosing seems to be important. While it is still being studied, taking alternate day aspirin does not seem to have the same protective effect (for <5 years of use, RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.85 to 1.01; for ≥5 years of use, RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.83 to 1.02). Associations were slightly stronger in analyses that used updated aspirin information from periodic follow-up questionnaires and included 3373 cancer deaths (for <5 years of use, RR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.76 to 0.94; for ≥5 years of use, RR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.75 to 0.95).

Conclusion These results are consistent with an association between recent daily aspirin use and modestly lower cancer mortality but suggest that any reduction in cancer mortality may be smaller than that observed with long-term aspirin use in the pooled trial analysis.

IntroductionA recent pooled analysis of randomized trials of daily aspirin for prevention of vascular events by Rothwell et al.[1]reported a statistically significant 15% reduction in overall cancer mortality during an intervention period of up to 10 years. The overall reduction in cancer mortality was mostly attributable to an estimated 37% reduction in cancer mortality during follow-up occurring after 5 years on aspirin (relative risk [RR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.49 to 0.82; 92 cancer deaths in the aspirin group compared with 142 in the control group). Similar effects were observed for lower doses, mostly 75–100mg/day, and higher doses (≥300mg/day).

In contrast to the pooled analysis of trials of daily aspirin,[1] two very large randomized trials of alternate-day aspirin observed no effect on overall cancer mortality,[2,3] raising questions about the frequency of aspirin use needed to reduce cancer risk. The Physicians' Health Study tested 325mg of aspirin every other day for 5 years and reported a relative risk of 1.16 (95% CI = 0.84 to 1.61, 79 cancer deaths on aspirin compared with 68 on placebo).[2] The Women's Health Study tested a lower dose (100mg every other day) for 10 years and reported a relative risk of 0.95 (95% CI = 0.81 to 1.11, 284 cancer deaths on aspirin compared with 299 on placebo).[3] Three large observational studies of aspirin use and cancer mortality reported mixed results,[4–6] although none of these studies examined aspirin use that was both long term and daily.

Results from the pooled trial analysis[1] potentially have very important implications. If these results are accurate and generalizable, people who begin a long-term regimen of daily low-dose aspirin and continue use for 5 years could reduce their subsequent risk of dying from cancer by more than a third. However, uncertainty remains about the magnitude of the effect of daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, on cancer mortality. In the pooled trial analysis,[1] the relative risk estimate for cancer mortality occurring during follow-up after the first 5 years was based on limited numbers and therefore included a relatively wide confidence interval. In addition, the magnitude of the association with overall cancer mortality is larger than might have been expected, given the absence of apparent effects on cancer mortality in large trials of aspirin taken every other day[2,3] and results from observational studies suggesting that aspirin use does not strongly reduce risk of cancers other than colorectal, esophageal, and stomach cancers.[7]

The purpose of this analysis was to quantify the association between daily aspirin use, particularly long-term use, and overall cancer mortality in the Cancer Prevention Study II (CPS-II) Nutrition Cohort, making use of detailed information on aspirin use collected at multiple time points. Because of the notable 37% reduction in cancer mortality observed in the pooled trial analysis during follow-up occurring after 5 years on daily aspirin,[1] we were particularly interested in cancer mortality among individuals in our cohort with a comparable history of aspirin exposure, that is, current daily aspirin users who had used aspirin during the preceding 5 years (referred to as current daily users of ≥5 years).

Copy of a medical journal article on ASA effects ( from two B.C. cardiologists)

Does an Aspirin a day keep the doctor away? Acetylsalicylic acid for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

Issue: BCMJ, Vol. 52, No. 6, July,

August 2010, page(s) 298 Articles

Michael Bayliss, MD, FRCPC, Andrew Ignaszewski, MD, FRCPC

More evidence is needed before ASA can be recommended for routine use to reduce the risk of CV disease, especially in women and diabetic patients.

Acetylsalicylic acid was introduced to the pharmaceutical market just over 100 years ago. Although it was originally intended for use as an analgesic, physicians quickly realized it provided many other therapeutic benefits. Dr Lawrence Craven first suggested ASA could prevent cardiovascular events with his publication of a large case series in 1950. Since then, several large randomized controlled trials involving more than 100000 patients have investigated the role of ASA for primary prevention of cardiovascular events.

These trials suggest that ASA provides modest protection at the expense of a small but real increase in bleeding. Based on these findings, several governing bodies have recommended using ASA for primary prevention. However, in light of recent studies, particularly in several selected subgroups, there continues to be debate regarding the use of ASA for preventing cardiovascular events.

The Greek physician Hippocrates was first to describe the analgesic effects of bark from the willow tree, a salicylate-containing plant. Although the mechanism through which willow bark relieved pain was not understood, it was used as an effective herbal remedy for over 2000 years.

In 1826, two Italian researchers, Brugnatelli and Fontana, successfully isolated the active compound, salicin.[1] Unfortunately, because of its significant gastrointestinal side effects, the compound’s clinical utility was limited.

In 1894, German chemist Felix Hoffman joined the Bayer Pharmaceutical Company. In search of a compound to relieve his father’s arthritis pain, he looked again at Brugnatelli and Fontana’s salacin, which had been further refined by chemists to produce pure salicylic acid.

By adding a buffer to the salicylic acid to create acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), Hoffman developed a compound that was better tolerated and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects.[2] In 1899, acetylsalicylic acid was released on the market and sold as “Aspirin.”

Although Bayer initially maintained that their compound had no effect on the heart, ASA would eventually become one of the most widely used medications for the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular (CV) disease.

Dr Lawrence Craven, a general practitioner from Glendale, California, first proposed that ASA could prevent myocardial infarctions after he noted increased bleeding rates in children who chewed ASA gum after tonsillectomy and tooth extractions.[3,4] In 1950, he published a case series of 400 patients prescribed ASA.5 After 2 years of follow-up, none of these patients had experienced a CV event.

Evidence for ASA continued to build in the 1960s and 1970s, although research was largely confined to the secondary prevention population. Studies suggested that ASA prevented 10 to 20 reinfarctions for every 1000 patients treated and had a small but significant effect on mortality.[6]

However, ASA use was also associated with a small increase in nonfatal bleeding. Given the lower CV risk in the primary prevention population, researchers questioned whether the benefits of ASA in this group would be significant enough to outweigh its adverse effects.

Early primary prevention trials

In the early 1980s, investigators from Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital

in Boston designed the Physicians’ Health Study, the first randomized controlled

trial to investigate ASA for the primary prevention of CV events.[7]

Over 260,000 American male physicians aged 40 to 84 were screened, with

22071 subjects eventually assigned to ASA (325 mg daily) or placebo arms. This

study was stopped early at 60 months because of a significant 44% relative risk

reduction (RRR) in MI. Although there was a 32% increase in risk of bleeding,

this increase was mostly attributed to easy bruising.

At approximately the same time that the Physicians’ Health Study was

underway, a group from Oxford University in England was conducting a large

randomized trial, the British Doctors’ Trial.[8]

Over 20000 invitations were mailed to healthy male doctors who had previously

responded to a smoking questionnaire. Ultimately, 5139 subjects were randomly

assigned to this open-label trial and asked to take ASA (500 mg daily) or

to avoid ASA. The results of this study failed to show any significant

difference in the incidence of nonfatal MI, stroke, or mortality.

Although the results from the British Doctors’ Trial conflicted with those of

the Physicians’ Health Study, it is important to note that the British trial was

open-labeled and had an event rate 3 times lower, consequently making it

significantly underpowered.

An overview of these two trials did suggest an overall 33% reduction in

the incidence of a first MI.[9] Based on this evidence, the Cardio-Renal Drugs

Advisory Committee recommended that the US Food and Drug Administration

approve professional labeling of ASA to reduce the risk of a first MI. However, the FDA did not follow this recommendation because the two trials were

interpreted to have divergent results.[10]

The Thrombosis Prevention Trial was a two-by-two factorial trial that

randomly assigned subjects to warfarin (goal INR 1.3–1.8), ASA (75 mg daily), or

a combination of the two.[11]

Acetylsalicylic acid and warfarin individually showed a 20% RRR in

ischemic heart disease, mostly driven by a reduction in nonfatal MI.

Although the combination of ASA and warfarin had a 34% RRR in MI, it was also

associated with a threefold increase in bleeding complications.

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study was designed to assess the

safety and efficacy of ASA in patients with hypertension, particularly in terms

of ASA’s effect on bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke.[12] Acetylsalicylic acid demonstrated a 15% RRR in major CV events. While a small increase in nonfatal major and minor bleeding was observed, there was no difference in fatal major bleeding.

Finally, the Primary Prevention Project recruited 4495 patients with one or

more cardiac risk factors from a general practitioner’s clinic and assigned

them to ASA (100 mg daily) or placebo.[13] This trial was stopped early because of a 23% RRR in CV events and a 44% reduction in cardiac death.

As in other studies, there was a small increase in bleeding complications

over the 3.6 years of follow-up (absolute risk increase 0.7%), mainly driven by

an increase in GI bleeds.

These five landmark trials found that using ASA was associated with a 15% to

44% Relative Risk Reduction of a first major CV event. Although bleeding rates were mildly increased, the events were mostly small and nonfatal.

Based on these results and subsequent meta-analyses, the American College of

Cardiology (ACC) recommended the use of ASA for the prevention of CV events in

patients who had a 10-year risk exceeding 10%.[14]

The US Preventive Services Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC) have made similar recommendations, endorsing ASA for primary

prevention in an intermediate- to high-risk population (Table).[15,16] However, the FDA has yet to approve professional labeling of ASA for this indication because of ongoing uncertainties and the need for more evidence, especially regarding women and

diabetic patients.

ASA in women

Cardiovascular disease is the largest single cause of death among women.[17] Despite this fact, only two of the five trials reviewed above enrolled women (HOT and the Primary Prevention Project). Subgroup analysis from these trials suggests that ASA did not provide women with protection from CV events.

Some have postulated that ASA may be ineffective in women because of male-female differences in salicylate metabolism or interactions with hormones.[18] However, only 180 of the 2402 CV events from all five of the primary prevention trials occurred in women, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions.

The Women’s Health Study set out to definitively answer questions of effectiveness of ASA in women.[19] In 1992, 1.7 million invitations were sent to female health professionals. Eligible subjects had to be older than 45 and have no history of CV disease.

After the completion of a 3-week run-in phase, a total of 39 876 women were

assigned to ASA (100 mg on alternate days) or placebo. After a follow-up of 10

years, there was no significant difference in the incidence of MI or mortality.

However, a significant 24% RRR in ischemic stroke was observed.

Although these results raise questions regarding the efficacy of ASA in

women, there are important details that should be highlighted. Women in this

study were generally younger than the male subjects enrolled in previous trials.

Only 10% of the participants were older than 65.

In this small subgroup there was a significant 26% RRR in major CV events,

suggesting a potential benefit in older women. Furthermore, only 24% of subjects

had more than one CV risk factor. The yearly major CV event rate was 0.26%,

indicating that this was a low-risk group of patients.

Finally, the dose of ASA used in this study was lower than in previous

studies, suggesting a higher dose might have been more effective. Despite the

lack of any substantial evidence suggesting a benefit in women, the ACC

guidelines still recommend ASA for all intermediate- to high-risk individuals

regardless of sex.

Emerging evidence

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration performed a meta-analysis using all of

the individual participant data from the primary prevention trials reviewed

above. The results of this study were published recently in The Lancet and

included over 95000 individuals with a total of 330000 person-years of

follow-up.[20]

The absolute risk of a serious vascular event per year was 0.51% in the ASA

group compared with 0.57% in the placebo group. This equates to a

statistically significant but clinically modest absolute risk reduction (ARR) of

0.06% and a relative risk reduction of 12%. Thus, 1666 patients would need to be

treated with ASA for a year to prevent one serious CV event.

Although the relative risk reduction of CV events is similar for both primary

and secondary prevention studies, the absolute risk reduction is much smaller in

the primary prevention population (ARR 0.06% vs. 1.49%). A small increase in

hemorrhagic stroke was seen in the ASA arm (0.04% vs. 0.03%), which was

counterbalanced by a small reduction in ischemic stroke.

There was also a small absolute increase in major bleeding of 0.03%. In

response to these disappointing results, the Antithrombotic Trialists’

Collaboration deemed ASA of uncertain value for primary prevention and stated

that the potential benefits with ASA needed to be carefully weighed against the

risk of major bleeding.

The recently published Aspirin for Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis Trial found

no evidence supporting the efficacy of ASA for primary prevention.[21] This study involved 3350 subjects aged 50 to 80 with an ankle brachial index of less than 0.95, an accepted surrogate for vascular disease.

After 8.2 years of follow-up there was no difference in the composite outcome

of fatal and nonfatal coronary event, stroke, or revascularization. However, as

observed with the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration, the yearly rate

of major bleeding was approximately 0.1%.

Researchers hope the results of two ongoing studies, ASPREE

(ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) and ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce the

Risk of Vascular Events) will provide some further insight.

ASA in diabetes

Patients with diabetes are known to be at increased risk for CV events, having a twofold to fivefold increase in risk of MI and stroke over the general population.[6,22]

Both the American National Cholesterol Education program and the ESC

guidelines consider diabetes to be a “coronary equivalent,” consequently placing

all diabetic patients into the high-risk category.[23,24] Diabetic patients are also known to have abnormal platelet function, including alterations in platelet

turnover, enhanced aggregation, and augmented thromboxane A2 synthesis (Figure).[25]

Antiplatelet agents are therefore a seemingly logical choice for reducing CV

events. Disappointingly, subgroup analysis from the primary prevention trials

and the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration have failed to show a

benefit in this population.[20,26]

There have been two large randomized trials investigating the

effectiveness of ASA in the diabetic population. The JPAD trial was a

multicentre randomized trial at 163 institutions throughout Japan.[27]

Because Japanese law prohibits the administration of a placebo in clinical

trials, this was an open-label trial. In addition to diabetes, 60% of subjects

had a history of smoking, 60% had hypertension, and 55% had a history of

dyslipidemia.

Despite this seemingly high-risk population, there was no significant

difference in CV events after just over 4 years of follow-up. However, the event

rate was 3 times lower than expected, which indicates that this group was

not as high-risk as expected, despite the presence of significant CV risk

factors.

The POPADAD trial was conducted by the Scotland Diabetic Registry Group.[28] This study randomly assigned diabetic patients with an ankle brachial index of less than 0.99 to ASA (100 mg daily) or placebo. Patients enrolled in this trial also had a significant burden of traditional CV risk factors.

Unfortunately, low enrollment and funding issues led to premature termination

of the study before a target sample size of 1600 was reached. After nearly 7

years of follow-up POPADAD failed to demonstrate a benefit in composite CV

outcomes. As in the JPAD trial, CV event rates were threefold lower than

originally predicted, again a surprising finding given the seemingly high-risk

population.

There are potentially many reasons ASA was not beneficial in these trials.

Both studies had a lower than predicted event rate and POPADAD fell

significantly short of its enrollment target. Consequently, they were both

underpowered for their primary outcome.

Patients may have also been “better treated,” limiting ASA’s ability to

reduce CV risk any further. Finally, diabetic patients may require higher doses

of ASA because of an increased turnover rate of thromboxane A2.

Despite the lack of evidence, many governing bodies continue to recommend ASA

for diabetic patients.[29] The ASCEND and ACCEPT D trials are currently

enrolling patients and aim to further investigate the effectiveness of ASA in

the diabetic population.

Conclusions

Acetylsalicylic acid is one of the most widely used preventive medications in the era of modern medicine.

Since Dr Craven proposed that the anticoagulant effect of ASA would

protect against CV disease, thousands of patients have been enrolled in several

large clinical trials. Overall, ASA appears to have only a modest reduction

(Absolute Risk Reduction of 0.06% per year) in the prevention of a first CV event, which is of

questionable clinical benefit.

Furthermore, there has been no evidence to date suggesting that ASA is of

benefit in either female or diabetic subgroups. The current guidelines continue

to endorse ASA for primary prevention in those at moderate to high risk of

cardiovascular disease.

Researchers hope that the results of several ongoing trials will provide us

with more insight into several unanswered questions and help further define the

patient population in which ASA should be used.

Issue: BCMJ, Vol. 52, No. 6, July,

August 2010, page(s) 298 Articles

Michael Bayliss, MD, FRCPC, Andrew Ignaszewski, MD, FRCPC

More evidence is needed before ASA can be recommended for routine use to reduce the risk of CV disease, especially in women and diabetic patients.

Acetylsalicylic acid was introduced to the pharmaceutical market just over 100 years ago. Although it was originally intended for use as an analgesic, physicians quickly realized it provided many other therapeutic benefits. Dr Lawrence Craven first suggested ASA could prevent cardiovascular events with his publication of a large case series in 1950. Since then, several large randomized controlled trials involving more than 100000 patients have investigated the role of ASA for primary prevention of cardiovascular events.

These trials suggest that ASA provides modest protection at the expense of a small but real increase in bleeding. Based on these findings, several governing bodies have recommended using ASA for primary prevention. However, in light of recent studies, particularly in several selected subgroups, there continues to be debate regarding the use of ASA for preventing cardiovascular events.

The Greek physician Hippocrates was first to describe the analgesic effects of bark from the willow tree, a salicylate-containing plant. Although the mechanism through which willow bark relieved pain was not understood, it was used as an effective herbal remedy for over 2000 years.

In 1826, two Italian researchers, Brugnatelli and Fontana, successfully isolated the active compound, salicin.[1] Unfortunately, because of its significant gastrointestinal side effects, the compound’s clinical utility was limited.

In 1894, German chemist Felix Hoffman joined the Bayer Pharmaceutical Company. In search of a compound to relieve his father’s arthritis pain, he looked again at Brugnatelli and Fontana’s salacin, which had been further refined by chemists to produce pure salicylic acid.

By adding a buffer to the salicylic acid to create acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), Hoffman developed a compound that was better tolerated and had fewer gastrointestinal side effects.[2] In 1899, acetylsalicylic acid was released on the market and sold as “Aspirin.”

Although Bayer initially maintained that their compound had no effect on the heart, ASA would eventually become one of the most widely used medications for the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular (CV) disease.

Dr Lawrence Craven, a general practitioner from Glendale, California, first proposed that ASA could prevent myocardial infarctions after he noted increased bleeding rates in children who chewed ASA gum after tonsillectomy and tooth extractions.[3,4] In 1950, he published a case series of 400 patients prescribed ASA.5 After 2 years of follow-up, none of these patients had experienced a CV event.

Evidence for ASA continued to build in the 1960s and 1970s, although research was largely confined to the secondary prevention population. Studies suggested that ASA prevented 10 to 20 reinfarctions for every 1000 patients treated and had a small but significant effect on mortality.[6]

However, ASA use was also associated with a small increase in nonfatal bleeding. Given the lower CV risk in the primary prevention population, researchers questioned whether the benefits of ASA in this group would be significant enough to outweigh its adverse effects.

Early primary prevention trials

In the early 1980s, investigators from Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital

in Boston designed the Physicians’ Health Study, the first randomized controlled

trial to investigate ASA for the primary prevention of CV events.[7]

Over 260,000 American male physicians aged 40 to 84 were screened, with

22071 subjects eventually assigned to ASA (325 mg daily) or placebo arms. This

study was stopped early at 60 months because of a significant 44% relative risk

reduction (RRR) in MI. Although there was a 32% increase in risk of bleeding,

this increase was mostly attributed to easy bruising.

At approximately the same time that the Physicians’ Health Study was

underway, a group from Oxford University in England was conducting a large

randomized trial, the British Doctors’ Trial.[8]

Over 20000 invitations were mailed to healthy male doctors who had previously

responded to a smoking questionnaire. Ultimately, 5139 subjects were randomly

assigned to this open-label trial and asked to take ASA (500 mg daily) or

to avoid ASA. The results of this study failed to show any significant

difference in the incidence of nonfatal MI, stroke, or mortality.

Although the results from the British Doctors’ Trial conflicted with those of

the Physicians’ Health Study, it is important to note that the British trial was

open-labeled and had an event rate 3 times lower, consequently making it

significantly underpowered.

An overview of these two trials did suggest an overall 33% reduction in

the incidence of a first MI.[9] Based on this evidence, the Cardio-Renal Drugs

Advisory Committee recommended that the US Food and Drug Administration

approve professional labeling of ASA to reduce the risk of a first MI. However, the FDA did not follow this recommendation because the two trials were

interpreted to have divergent results.[10]

The Thrombosis Prevention Trial was a two-by-two factorial trial that

randomly assigned subjects to warfarin (goal INR 1.3–1.8), ASA (75 mg daily), or

a combination of the two.[11]

Acetylsalicylic acid and warfarin individually showed a 20% RRR in

ischemic heart disease, mostly driven by a reduction in nonfatal MI.

Although the combination of ASA and warfarin had a 34% RRR in MI, it was also

associated with a threefold increase in bleeding complications.

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study was designed to assess the

safety and efficacy of ASA in patients with hypertension, particularly in terms

of ASA’s effect on bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke.[12] Acetylsalicylic acid demonstrated a 15% RRR in major CV events. While a small increase in nonfatal major and minor bleeding was observed, there was no difference in fatal major bleeding.

Finally, the Primary Prevention Project recruited 4495 patients with one or

more cardiac risk factors from a general practitioner’s clinic and assigned

them to ASA (100 mg daily) or placebo.[13] This trial was stopped early because of a 23% RRR in CV events and a 44% reduction in cardiac death.

As in other studies, there was a small increase in bleeding complications

over the 3.6 years of follow-up (absolute risk increase 0.7%), mainly driven by

an increase in GI bleeds.

These five landmark trials found that using ASA was associated with a 15% to

44% Relative Risk Reduction of a first major CV event. Although bleeding rates were mildly increased, the events were mostly small and nonfatal.

Based on these results and subsequent meta-analyses, the American College of

Cardiology (ACC) recommended the use of ASA for the prevention of CV events in

patients who had a 10-year risk exceeding 10%.[14]

The US Preventive Services Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC) have made similar recommendations, endorsing ASA for primary

prevention in an intermediate- to high-risk population (Table).[15,16] However, the FDA has yet to approve professional labeling of ASA for this indication because of ongoing uncertainties and the need for more evidence, especially regarding women and

diabetic patients.

ASA in women

Cardiovascular disease is the largest single cause of death among women.[17] Despite this fact, only two of the five trials reviewed above enrolled women (HOT and the Primary Prevention Project). Subgroup analysis from these trials suggests that ASA did not provide women with protection from CV events.

Some have postulated that ASA may be ineffective in women because of male-female differences in salicylate metabolism or interactions with hormones.[18] However, only 180 of the 2402 CV events from all five of the primary prevention trials occurred in women, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions.

The Women’s Health Study set out to definitively answer questions of effectiveness of ASA in women.[19] In 1992, 1.7 million invitations were sent to female health professionals. Eligible subjects had to be older than 45 and have no history of CV disease.

After the completion of a 3-week run-in phase, a total of 39 876 women were

assigned to ASA (100 mg on alternate days) or placebo. After a follow-up of 10

years, there was no significant difference in the incidence of MI or mortality.

However, a significant 24% RRR in ischemic stroke was observed.

Although these results raise questions regarding the efficacy of ASA in

women, there are important details that should be highlighted. Women in this

study were generally younger than the male subjects enrolled in previous trials.

Only 10% of the participants were older than 65.

In this small subgroup there was a significant 26% RRR in major CV events,

suggesting a potential benefit in older women. Furthermore, only 24% of subjects

had more than one CV risk factor. The yearly major CV event rate was 0.26%,

indicating that this was a low-risk group of patients.

Finally, the dose of ASA used in this study was lower than in previous

studies, suggesting a higher dose might have been more effective. Despite the

lack of any substantial evidence suggesting a benefit in women, the ACC

guidelines still recommend ASA for all intermediate- to high-risk individuals

regardless of sex.

Emerging evidence

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration performed a meta-analysis using all of

the individual participant data from the primary prevention trials reviewed

above. The results of this study were published recently in The Lancet and

included over 95000 individuals with a total of 330000 person-years of

follow-up.[20]

The absolute risk of a serious vascular event per year was 0.51% in the ASA

group compared with 0.57% in the placebo group. This equates to a

statistically significant but clinically modest absolute risk reduction (ARR) of

0.06% and a relative risk reduction of 12%. Thus, 1666 patients would need to be

treated with ASA for a year to prevent one serious CV event.

Although the relative risk reduction of CV events is similar for both primary

and secondary prevention studies, the absolute risk reduction is much smaller in

the primary prevention population (ARR 0.06% vs. 1.49%). A small increase in

hemorrhagic stroke was seen in the ASA arm (0.04% vs. 0.03%), which was

counterbalanced by a small reduction in ischemic stroke.

There was also a small absolute increase in major bleeding of 0.03%. In

response to these disappointing results, the Antithrombotic Trialists’

Collaboration deemed ASA of uncertain value for primary prevention and stated

that the potential benefits with ASA needed to be carefully weighed against the

risk of major bleeding.

The recently published Aspirin for Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis Trial found

no evidence supporting the efficacy of ASA for primary prevention.[21] This study involved 3350 subjects aged 50 to 80 with an ankle brachial index of less than 0.95, an accepted surrogate for vascular disease.

After 8.2 years of follow-up there was no difference in the composite outcome

of fatal and nonfatal coronary event, stroke, or revascularization. However, as

observed with the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration, the yearly rate

of major bleeding was approximately 0.1%.

Researchers hope the results of two ongoing studies, ASPREE

(ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) and ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce the

Risk of Vascular Events) will provide some further insight.

ASA in diabetes

Patients with diabetes are known to be at increased risk for CV events, having a twofold to fivefold increase in risk of MI and stroke over the general population.[6,22]

Both the American National Cholesterol Education program and the ESC

guidelines consider diabetes to be a “coronary equivalent,” consequently placing

all diabetic patients into the high-risk category.[23,24] Diabetic patients are also known to have abnormal platelet function, including alterations in platelet

turnover, enhanced aggregation, and augmented thromboxane A2 synthesis (Figure).[25]

Antiplatelet agents are therefore a seemingly logical choice for reducing CV

events. Disappointingly, subgroup analysis from the primary prevention trials

and the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration have failed to show a

benefit in this population.[20,26]

There have been two large randomized trials investigating the

effectiveness of ASA in the diabetic population. The JPAD trial was a

multicentre randomized trial at 163 institutions throughout Japan.[27]

Because Japanese law prohibits the administration of a placebo in clinical

trials, this was an open-label trial. In addition to diabetes, 60% of subjects

had a history of smoking, 60% had hypertension, and 55% had a history of

dyslipidemia.

Despite this seemingly high-risk population, there was no significant

difference in CV events after just over 4 years of follow-up. However, the event

rate was 3 times lower than expected, which indicates that this group was

not as high-risk as expected, despite the presence of significant CV risk

factors.

The POPADAD trial was conducted by the Scotland Diabetic Registry Group.[28] This study randomly assigned diabetic patients with an ankle brachial index of less than 0.99 to ASA (100 mg daily) or placebo. Patients enrolled in this trial also had a significant burden of traditional CV risk factors.

Unfortunately, low enrollment and funding issues led to premature termination

of the study before a target sample size of 1600 was reached. After nearly 7

years of follow-up POPADAD failed to demonstrate a benefit in composite CV

outcomes. As in the JPAD trial, CV event rates were threefold lower than

originally predicted, again a surprising finding given the seemingly high-risk

population.

There are potentially many reasons ASA was not beneficial in these trials.

Both studies had a lower than predicted event rate and POPADAD fell

significantly short of its enrollment target. Consequently, they were both

underpowered for their primary outcome.

Patients may have also been “better treated,” limiting ASA’s ability to

reduce CV risk any further. Finally, diabetic patients may require higher doses

of ASA because of an increased turnover rate of thromboxane A2.

Despite the lack of evidence, many governing bodies continue to recommend ASA

for diabetic patients.[29] The ASCEND and ACCEPT D trials are currently

enrolling patients and aim to further investigate the effectiveness of ASA in

the diabetic population.

Conclusions

Acetylsalicylic acid is one of the most widely used preventive medications in the era of modern medicine.

Since Dr Craven proposed that the anticoagulant effect of ASA would

protect against CV disease, thousands of patients have been enrolled in several

large clinical trials. Overall, ASA appears to have only a modest reduction

(Absolute Risk Reduction of 0.06% per year) in the prevention of a first CV event, which is of

questionable clinical benefit.

Furthermore, there has been no evidence to date suggesting that ASA is of

benefit in either female or diabetic subgroups. The current guidelines continue

to endorse ASA for primary prevention in those at moderate to high risk of

cardiovascular disease.

Researchers hope that the results of several ongoing trials will provide us

with more insight into several unanswered questions and help further define the

patient population in which ASA should be used.

Table of ASA Risks

.

ASA Desensitization

Some people are "sensitive" to aspirin.

Among them are people with asthma, sinusitis, and nasal polyps.

Giving these people aspirin can trigger allergic type symptoms.

I once gave a patient with asthma an interesting evening of wheezing in the ER while I fixed the symptoms that the aspirin I had given him earlier in the day had caused.

ASA sensitivity is not a true allergy, so doing allergy tests and getting allergy shots doesn't work. The easiest way to sort it out is to give a "sensitive" patient progressively large doses of aspirin over a day or two, while standing by to fix any semi-scary side effects that might happen. Just as I did that night in emergency ! By accident.

Once a person has been desensitized to aspirin, they have to take aspirin every day to maintain their tolerance to aspirine. If they stop taking it ever for a few days, the sensitively comes back, and they have to be desensitized all over again.

A big nuisance, but occasionally worth it, because aspirin is so useful in so many ways. ( Plus someone who is sensitive to aspirin is usually sensitive to all other anti-inflammatory medications too. This means ibuprofen, naproxen, indomethasin, diclofenac , .....

All except for acetominophen ( Tylenol ). Acetominophen is an outsider that doesn't play by the same rules as all the other inflammatories. Even people with aspirin allergy can take acetominopen by the bucket without any ill effects. And sometimes we actually recommend it !

Among them are people with asthma, sinusitis, and nasal polyps.

Giving these people aspirin can trigger allergic type symptoms.

I once gave a patient with asthma an interesting evening of wheezing in the ER while I fixed the symptoms that the aspirin I had given him earlier in the day had caused.

ASA sensitivity is not a true allergy, so doing allergy tests and getting allergy shots doesn't work. The easiest way to sort it out is to give a "sensitive" patient progressively large doses of aspirin over a day or two, while standing by to fix any semi-scary side effects that might happen. Just as I did that night in emergency ! By accident.

Once a person has been desensitized to aspirin, they have to take aspirin every day to maintain their tolerance to aspirine. If they stop taking it ever for a few days, the sensitively comes back, and they have to be desensitized all over again.

A big nuisance, but occasionally worth it, because aspirin is so useful in so many ways. ( Plus someone who is sensitive to aspirin is usually sensitive to all other anti-inflammatory medications too. This means ibuprofen, naproxen, indomethasin, diclofenac , .....

All except for acetominophen ( Tylenol ). Acetominophen is an outsider that doesn't play by the same rules as all the other inflammatories. Even people with aspirin allergy can take acetominopen by the bucket without any ill effects. And sometimes we actually recommend it !